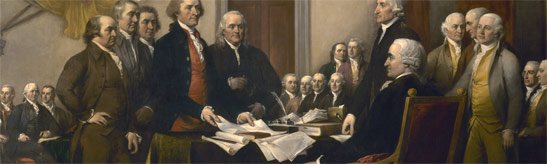

The Signers of the Declaration of Independence

As we read the newspapers and other printed materials, listen to television and radio, and read or hear the voices of distinguished Americans, we become conscious that America is at the crossroads. We stand today with the reality before us that we could lose our great heritage of freedom.

There are those in our midst who depreciate our great beloved republic and the men who laid the foundation of our government. These are the voices and the words that our youth frequently hear or read. I ask, How can they be expected to feel a duty to God and their country when the climate of opinion is so negative to all that we cherish and hold dear? The answer to that question will be decided by how well our homes instill a love of God and of our country and how well we as leaders exemplify before our youth our devotion. When was the last time you took the occasion to let them know your feelings about your country?

This nation is unlike any other nation. It was uniquely born. It had its beginning when fifty-six men affixed their signatures to the Declaration of Independence. I realize there are some who view that declaration as only a political document. It is much more than that. It constitutes a spiritual manifesto, declaring not for this nation alone, but for all nations, the source of man’s rights.

The purpose of the declaration was to set forth the moral justifications of a rebellion against a long-recognized political tradition—the divine right of kings. At issue was the fundamental question of whether men’s rights were God-given or whether these rights were to be dispensed by governments to their subjects. This document proclaimed that all men have certain inalienable rights; in other words, that those rights came from God. The colonists were therefore not rebels against political authority. Their contention was not with Parliament nor the British people; it was against a tyrannical monarch who had “conspired,” “incited,” and “plundered” them. They were thus morally justified to revolt, for as it was stated in the declaration, “when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”

The document concludes with this pledge: “For the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the Protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.”

How prophetic that pledge was to be! Consider with me some of the sacrifices made by these signers.

Fifty-six men signed the document on August 2, 1776, or in the case of some, shortly thereafter. They came from all walks of life. Twenty-three were lawyers, twelve were merchants, twelve were men of the soil, four were physicians, two were manufacturers, one was a politician, one a printer, and another a minister.

Almost a third of the signers were under forty years of age; eighteen were in their thirties and three were in their twenties. Only seven were over sixty. The youngest, Edward Rutledge of South Carolina, was twenty-six and a half, and the oldest, Benjamin Franklin, was seventy. Three of the signers lived to be over ninety. Charles Carroll died at age ninety-five. Ten died in their eighties.

Possibly as many as six of the signers were childless in their marriages (two never did marry), but the remainder sired 325 children. Carter Braxton had 18 children; William Ellery, 17; and Robert Sherman, 15.

The signers were religious men, all being Protestant except Charles Carroll, who was Roman Catholic. Over half expressed their religious faith as being Episcopalian. Others were Congregational, Presbyterian, Quaker, and Baptist.

Two of the signers would become presidents of the United States—Thomas Jefferson, the author of the declaration, and John Adams. Two—John Adams and Benjamin Harrison—would be fathers of future presidents. Another, Elbridge Gerry, was the vice-president under James Madison.

Those signers pledged their lives, and some paid that price for this nation’s birth—and our birthright.

At least nine of them died as a result of the war or its hardships on them. The first of the signers to die was John Morton of Pennsylvania. He was at first sympathetic to the British, but finally changed his mind and cast his vote for independence. By doing so, his friends, relatives, and neighbors turned against him. Those who knew him best said this ostracism hastened his death, for he lived only eight months after the signing. His last words were, “. . . tell them that they will live to see the hour when they shall acknowledge it to have been the most glorious service that I ever rendered to my country.”

Another to pay with his life was Caesar Rodney. Suffering facial cancer, he left his sickbed at midnight and rode all night by horseback through a severe storm. He arrived just in time to cast the deciding vote for his delegation in favor of independence. His doctors told him he needed treatment obtainable only in Europe. He refused to go in this time of his country’s crisis. The decision cost him his life.

When the British came to Trenton, they settled near the home of John Hart, one of the five signers from New Jersey. He had a large farm and several grist mills. While his wife was on her deathbed, Hessian soldiers descended on Hart’s property. They destroyed his mills, ravaged his property, and scattered his thirteen children. Hart became a hunted fugitive. When he finally returned to his land, he was broken in health, his farmland was scourged, his wife had died, and his children were all scattered. He died three years after signing the declaration.

Yes, the signers also pledged their fortunes, and at least fifteen saw the realization of that pledge. Twelve had their homes ransacked or ruined. Six literally gave their fortunes to further the cause. When the four New York delegates signed the declaration, they signed away their property. William Floyd was exiled from his home for seven years and was practically ruined financially. Francis Lewis had his home plundered and burned, and his wife was carried away prisoner. She suffered great brutality and never regained her health; she died within two years. He never regained his fortune. Robert Morris had his property destroyed and, like Floyd, was denied his home for seven years. Phillip Livingston never saw his home again, for his estate became a British naval hospital. He sold all of his remaining property to finance the revolution. He died before the war was over.

Another signer, merchant Robert Morris, lost 150 ships, which were sunk during the war. Three of the four signers from South Carolina—Thomas Heyward, Arthur Middleton, and Edward Rutledge—were taken prisoner by the British and imprisoned for ten months.

Thomas Nelson, Jr., of Virginia died in poverty at age fifty-one. He gave his fortune to help finance the war and never regained either it or his health. Before Patrick Henry gave his great speech, he was preceded by Nelson who said, “I am a merchant of Yorktown, but I am a Virginian first. Let my trade perish. I call God to witness that if any British troops are landed in the County of Yorks, of which I am a Lieutenant, I will wait no order, but will summon the militia and drive the invaders into the sea.”

When Patrick Henry declared his immortal words, “. . . give me liberty or give me death,” he was not speaking idly. When those signers affixed their signatures to that sacred document, they were, in a real sense, choosing liberty or death, for if the revolution failed, if their fight had come to naught, they would be hanged as traitors.

Yes, the signers fulfilled their pledge. Their spirit of sacrifice was exemplified by John Adams, who, when others were vacillating on whether to adopt the declaration, declared:

“Sink or swim, live or die, survive or perish, I give my hand and my heart to this vote. It is true, indeed, that in the beginning we aimed not at independence. But there’s a Divinity which shapes our ends. . . . Why, then, should we defer the Declaration? . . .

“. . . You and I, indeed, may rue it. We may not live to the time when this Declaration shall be made good. We may die; die colonists; die slaves; die, it may be, ignominiously and on the scaffold. Be it so, Be it so. If it be the pleasure of Heaven that my country shall require the poor offering of my life, the victim shall be ready. . . . But while I do live, let me have a country, or at least the hope of a country, and that a free country.

“But whatever may be our fate, be assured . . . that this Declaration will stand. It may cost treasure, and it may cost blood; but it will stand, and it will richly compensate for both. Through the thick gloom of the present, I see the brightness of the future, as the sun in heaven. We shall make this a glorious, an immortal day. When we are in our graves, our children will honor it. They will celebrate it with thanksgiving, with festivity, with bonfires, and illuminations. On its annual return they will shed tears, copious, gushing tears, not of subjection and slavery, not of agony and distress, but of exultation, of gratitude, and of joy. Sir, before God, I believe the hour is come. My judgment approves this measure, and my whole heart is in it. All that I have, and all that I am, and all that I hope, in this life, I am now ready here to stake upon it; and I leave off as I begun, that live or die, survive or perish, I am for the Declaration. It is my living sentiment, and by the blessing of God it shall be my dying sentiment, Independence, now, and Independence for ever.” (The Works of Daniel Webster, 4th ed., 1851, 1:133-36.)

How fitting it is that we sing in “America the Beautiful”:

O beautiful for heroes proved In liberating strife, Who more than self their country loved, And mercy more than life!

These patriots were willing to make the effort and sacrifice they did because they understood a fundamental that seems to be forgotten today: that the rights of man are either God-given as part of a divine plan or they are granted as part of a political plan. Reason, necessity, and religious conviction and belief in the sovereignty of God led these men to accept the divine origin of man’s rights. To God’s glory, and the credit of these men, our nation had its unique birth.

If we accept the premise that human rights are granted by government, then we must be willing to accept the corollary that they can be denied by government. If Americans should ever come to believe that their rights and freedoms are instituted among men by politicians and bureaucrats, then they will no longer carry the proud inheritance of their forefathers, but will grovel before their masters seeking favors and dispensations—a throwback to the feudal system of the Dark Ages. We must ever keep in mind the inspired words of Thomas Jefferson, as found in the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

Since God created man with certain inalienable rights, and man, in turn, created government to help secure and safeguard those rights, it follows that man is superior to government and should remain master over it, not the other way around. As said so appropriately by Lord Action:

“It was from America that the plain ideas that men ought to mind their own business, and that the nation is responsible to Heaven for the acts of the State,—ideas long locked in the breast of solitary thinkers, and hidden among Latin folios,—burst forth like a conqueror upon the world they were destined to transform, under the title of the Rights of Man. . . .

“. . . and the principle gained ground, that a nation can never abandon its fate to an authority it cannot control.” (The History of Freedom and Other Essays, 1907, pp. 55-56.)

We also need to keep before us the truth that people who do not master themselves and their appetites will soon be mastered by government.

I wonder if we are not rearing a generation that seemingly does not understand this fundamental principle. Yet this is the principle that separates our country from all others. The central issue before the people today is the same issue that inflamed the hearts of our Founding Fathers in 1776 to strike out for independence. That issue is whether the individual exists for the state or whether the state exists for the individual.

In a republic, the real danger is that we may slowly slide into a condition of slavery of the individual to the state rather than entering this condition by a sudden revolution. The loss of our liberties might easily come about, not through the ballot box, but through the abandonment of the fundamental teachings from God and this basic principle upon which our country was founded. Such a condition is usually brought about by a series of little steps which, at the time, seem justified by a variety of reasons.

Yes, I thank God for the sacrifices and efforts made by our Founding Fathers, whose efforts brought us the blessings we have today. Their lives should be reminders to us that we are blessed beneficiaries of a liberty earned by great sacrifice of property, reputation, and life. There should be no doubt what our task is today. If we truly cherish the freedoms we have, we must instill these sacred principles in the hearts and minds of our youth. We have the obligation to rekindle the flame that existed two hundred years ago among those who pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor. The opportunity for patriots to do so again is clearly upon us.

(Source: This Nation Shall Endure, Ezra Taft Benson, published 1977)